Dear Friends and Colleagues,

“In the midst of life we are in death.”

Here’s a challenge for you to consider while you read this article (or scoot straight to the last few paragraphs, if you don’t want to read it all!) where does this verse come from? Old Testament? New Testament? Somewhere else?

This old familiar phrase came to me (as I’m sure it did to many) in the aftermath of the total loss of all 157 souls on board the Ethiopian Airways flight ET 302 from Addis Ababa’s Bole Airport to JKIA Nairobi on Sunday 10 March.

Perhaps most of us don’t know (I certainly didn’t until recently) that Ethiopian is one of the biggest carriers in Africa by fleet size (carrying 10.6 million passengers in 2018). It has tripled its passenger numbers over the past decade and is in the middle of a significant expansion, aiming to double its fleet by 2025 to 120 to secure its place as Africa’s biggest airline. A new terminal recently opened at Bole, tripling the airport’s size. Ethiopian has only recently started flying from here in Manchester. My IACAC Exec colleague, Pierre de Mareuil chose to fly with Ethiopian from CDG to our Board meeting in Nairobi (taking the route via Addis Ababa). Just over a week after returning from Nairobi myself, I have felt more than usually connected to this disaster, and to all our colleagues at JKIA and Wilson Airport in Nairobi

This was not a “two-bit” airline flying “on a wing and a prayer”, but a brand new aircraft (a Boeing 737 Max 8) flying from a new terminal, with experienced and skilled flight crew.

And this was not a small local incident, but a globally significant bereavement – as well as personal tragedy for the families, friends and colleagues of each person on board. Passengers and crew came from more than 30 nationalities. According to the airline, 32 Kenyans perished; 18 Canadians, nine Ethiopians, eight from Italy, from China and from the USA, seven from the UK and from France, six Egyptians, five from the Netherlands, four from India and from Slovakia, and three from Sweden and from Russia, with Germany, Austria, Spain, Israel, Morocco, Poland, Belgium, Nigeria, Indonesia, Serbia, Djibouti, Somalia, Uganda, Yemen, Sudan, Togo, and Mozambique also mourning the loss of citizens in the accident. The individual impact of such incidents was brought home in these few words: “We’re just waiting for my mum,” said Wendy Otieno, clutching her phone and weeping. “We’re just hoping she took a different flight or was delayed. She’s not picking up her phone.”

Only five days later, the terrorist attack upon two Mosques at Friday prayers in New Zealand was to prove another globally significant bereavement. In response, New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has given a strong lead to the rest of the world to take seriously the growing phenomenon of Islamophobic terrorist violence. Ardern was clear to characterise the shootings not as an attack on her country and her people, but as a symptom of a global trend that needs to be addressed: “What New Zealand experienced here was violence brought against us by someone who grew up and learned their ideology somewhere else. If we want to make sure globally that we are a safe and tolerant and inclusive world we cannot think about this in terms of boundaries.” As airport chaplains, we are among the goodly fellowship of global custodians of inter-religious engagement, and the way we encourage those of different faiths to encounter, engage with (and love) one another can make a significant difference.

But even the UK even mainstream newspaper columnists are keen to tell us that the use of the term Islamophobia “is a fiction used to shut down debate” (Melanie Phillips in the (London) Times May 7, 2018). Whenever a human being is vilified, attacked or killed because of their religious faith, ethnicity, culture, sexuality, ability/disability, nationality; that is something that needs to be acknowledged and vigorously challenged. I’m grateful to New Zealand, a country that is apparently often missed off maps of the world but whose leaders and population have responded to such an outrage with wisdom, compassion, and the moral and political leadership of a country a hundred times the size.

Islamophobia is abhorrent, antisemitism is abhorrent, all forms of hatred are abhorrent. The terrorist attack in Utrecht only three days later, on March 18, demonstrates the truth of the maxim (first articulated in the Canadian parliament in 1914, often attributed to Gandhi, and quoted most memorably in Joseph Stein’s screenplay for ‘Fiddler on the Roof’): “(Villager) We should defend ourselves. An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”

(Tevye): “Very good. And that way, the whole world will be blind and toothless.”

“In the midst of life we are in death.” – where is that phrase from? I don’t know, though its meaning is all too real.

On Monday April 29 (the day following International Workers’ Memorial Day Sunday April 28, 2019) staff in Manchester will gather in the Garden of Remembrance to recall with thanksgiving every member of our airport community who has died in the last twelve months. The youngest employee to die in post this past year was only 22. Sometimes we didn’t get a chance to say goodbye. On at least one occasion, it was airport colleagues who (in the absence of family or neighbours) were the ones who nursed and cared for their friend and co-worker through his last days and nights.

I know that IWMD is observed around the globe. At Manchester airport it has grown thanks to the enthusiasm of Trade Unions and the support of Airport management – in enthusiastic partnership with the Chaplaincy. In many places the focus is on the safety, health and well-being of employees, challenging unsafe practices and sometimes flagrant health and safety violations. A motto of the IWMD movement is: “Remember the dead, fight for the living”. That’s a complex task. Meeting a manager at one of the construction sites at Manchester Airport last month, I was told that six times as many construction workers take their own lives than die as a result of workplace accidents. Therefore, the company has made it a huge focus of their work to support good mental health and staff relationships. Airports generally have outstanding safety records, and, with fewer industrial fatalities, it is good that we remember all who have died, in service or in retirement after years of service. If you’d be interested in seeing the order of service from last year’s observance in Manchester, please – just ask, and if you have any you’d like to contribute, please share.

And finally, I was so sad to hear of the death of our friend and colleague Father Glenn O Connor of Indianapolis. Others have offered tributes to Fr Glenn, and would just like to offer my own. The first few days at my first IACAC conference in Atlanta in 2013 were (understandably) slightly overwhelming; lots of people who seemed to know everyone else, but on the first evening, after the opening ceremony, there were a number who had been at the end of the queue for the buffet reception who gathered in the hotel’s restaurant to supplement their calorific intake – so I found myself at the same table as Father Glenn. To be in his presence was to experience the warm glow of humour, laughter, welcome and hospitality – all key to the life of a parish priest and an airport chaplain. May he rest in peace and rise in glory, and may God bring comfort to his family and his many friends and colleagues.

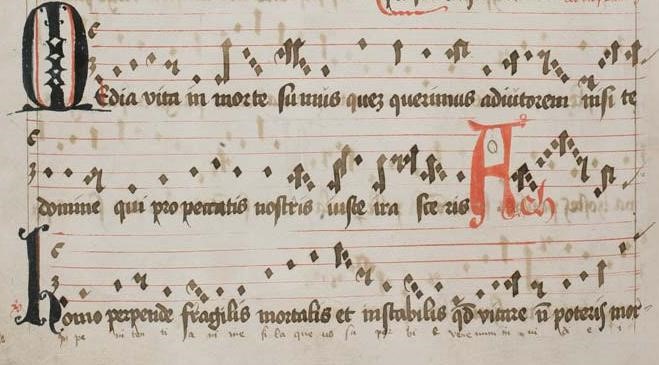

Well, back to those words: “In the midst of life we are in death” (in Latin: Media vita in morte sumus). Though a part of the Thomas Cranmer’s English Prayer Book Burial Service (borrowed from fellow bishop Miles Coverdale’s poetic rendering of Martin Luther’s 1524, “Mytten wir ym leben synd”), the source is not the Bible, but seems to be from a battle song of 912 by Notker the Stammerer, a monk of the Benedictine abbey of Saint Gallen in Switzerland. It formed the first line of a Gregorian chant for a New Year service in the 1300s.

From Switzerland, via Germany to England, and my own part of the world, the York Breviary, which used the words at (the monastic service of) Compline for the Fourth Sunday in Lent (Laetare (“Rejoice”) Sunday). The words have also been sung as a hymn to ask for God’s help in times of public need.

As March comes ‘in like a lion and out like a lamb’ (though in the UK of the twenty-first century, the opposite is at least as likely to be true, with White (i.e. snowy) Easters outnumbering White Christmases in England this past decade!) Western Christians are mid–Lent (as I write), already looking forward to Easter, and there are a whole batch of Spring and New Year festivals in northern hemisphere (and autumn festivals in the southern).

To misquote a popular phrase from American fantasy drama HBO series: ‘Spring is coming’ (to those in the Southern hemisphere… in about six months’ time!). Lent is Christian season of fasting and penitence, but it originates simply as a preparation for the joyful celebrations of Jesus’ resurrection. The Old English word “lencten” (Middle Dutch “lentin”, Old High German “lengizin”) means simply “the time of the lengthening of days and of growth in the natural world.”

In the midst of Lent, and in the midst of many troubles across the world, and in the midst of personal sadness, History and Tradition call us to pray for peace and fullness of life for all; to witness to hope, and to model reconciliation between the peoples of the world (and what better place to start than in the multi-faith prayer spaces of international airports?):

In the midst of life we are in death. Of whom may we seek for succour, but of thee, O Lord, who for our sins art justly displeased?

Yet, O Lord God most holy, O Lord most mighty, O holy and most merciful Saviour, deliver us not into the bitter pains of eternal death.

Notker the Stammerer, 912 (?)

The Revd George Lane

IACAC President

Download the whole March 2019 Newsletter: